Rejecting the tyranny of "inhuman" time

If the past no longer is, and the future has yet to be, we can only live in the present. The present is the only time in which we can do something, the only time in which we really exist.

The word ‘tempus’ – Latin for time – means ‘the division of duration’, in other words, a moment or an instant. Time is an elusive phenomenon that humankind has always tried to define or measure in order to understand it. “The present,” said Saint Augustine, “is already in the past when we begin to talk about it.” This is even more true if we consider time as a subjective phenomenon that depends on how an individual feels about it. It is a continuum that is difficult to divide into separate moments and which can be experienced by each person differently.

This fixed understanding of time was set in stone, by science, too, until Albert Einstein published his theory of general relativity. From that point, we understood that ‘objective’ time, like ‘subjective’ time, is variable, since it depends on the speed at which the observer is moving as well as gravitational forces.

The mark of human finiteness

Quantifying time and dividing it into portions was an opportunity to seize it, if not fully understand it. It led to a better understanding of an anxiety-provoking phenomenon, namely that time is a reminder of humankind’s finiteness and mortality. Seventeenth-century French philosopher Pascal held that this was why people could not remain at rest but rather had to be constantly busy, always looking to the future. He called this ‘distraction’. If people remained idle, confronted with their consciousness, the idea of their own finiteness would be intolerable.

An inhuman tempo

For many present-day thinkers, Pascal’s theory is more relevant than ever. Contemporary French philosopher, Olivier Abel, for example, explains on his website (in French) that these days there is still an intense feeling that all time does is cause damage and lead us towards our own end. As a palliative, therefore, we make our lives more complicated and multiply not only the choices and possibilities available to us, but also our connections with others.

The technological innovations that have burgeoned in recent years only accentuate this phenomenon, which makes our present very ‘jittery’, as Olivier Abel would say. “Speed is faster, transport is faster, we move from place to place faster, we connect with people more and more frequently and we end up finding that normal, unavoidable,” he explains. “Yet there is a limit because of human finiteness, both physical and mental.” Olivier Abel believes that time is becoming ‘inhuman’ because ‘we are in a situation where technological change is exceeding the limits of the human condition’.

The fundamental value of time

Slowing down has therefore become a matter of urgency if we are to evolve at a more ‘human’ tempo. This means restoring the value of time, in particular by ensuring that we can rely on a broader relationship with time, whether we are looking to the past or to the future.

At Banque de Luxembourg, we try to do this every day through our services. It is an attitude that has carried our institution through almost a century (we were founded in 1920) and can been seen in our pursuit of long-term investment strategies that avoid passing fads. We have been rigorously applying these investment principles for more than 20 years. Our approach to wealth management is characterised by great stability, whether in our teams or in our ongoing commitment to philanthropy and sponsorship.

In addition to the way in which we manage wealth and interact with our employees, the value we place on time can be seen in the experience we offer our clients. For example, we refuse to pursue an aggressive sales policy. Instead we spend as much time with our clients as needed and offer them reliable, long-term solutions. We are also aware that each client has their own story and that the wealth they entrust to us is part of that story. For example, it may be part of their inheritance. Our rigorous approach means that, ultimately, we save our clients time. Because we know how precious time is.

Valuing time without living in the past

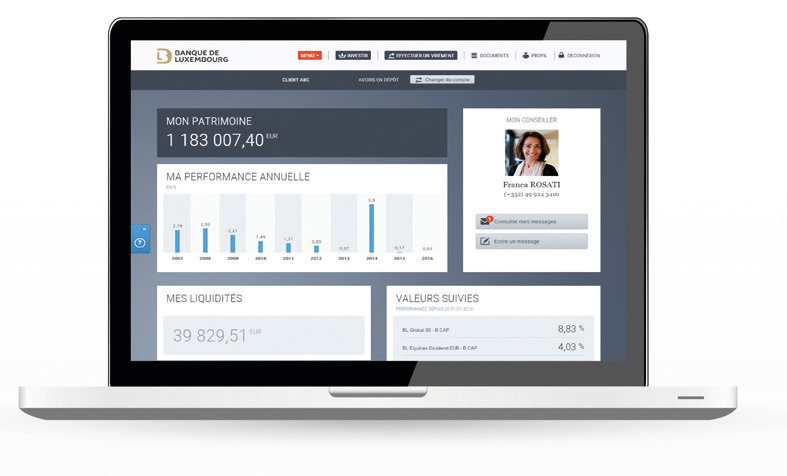

In private banking, the challenges of digital technology clearly matter, but they must not overshadow the importance we give to people and the value we give to time. In addition to the online banking services we offer, particularly for wealth management and advice, we have equipped our advisers with tablets so they can complete the MiFID questionnaire online and present the breakdown and performance of clients’ assets for any given period in real time. In this way we are enhancing the interaction between adviser and client, rather than eliminating it.

At Banque de Luxembourg, there is no dichotomy between digital technology and people. On the contrary, new technologies make it possible to optimise personal interaction at a very human pace.